|

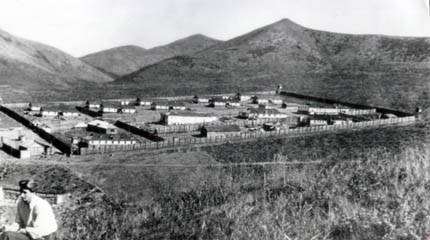

Last years of GULAG

|

A prisoner’s story

One of the prisoners at the time was a drama student by the name of Yuri Lvovich Fidelgolts. It might sound Jewish name but in fact he was Russian orthodox. In 1948, Fidelgolts was removed from his studies for writing “subversive” poems in his diary. Thanks to his parents’ status as doctors for the party elite, his case came before a normal court and he was defended by a lawyer his parents had engaged. The judge said it was a waste of money as the lawyer could not help him.

The judgment was lenient. “Only” ten years hard labour at a time when quarters and halves were the standard in the Soviet Union. A quarter was 25 years, a half 50.

Fidelgolts was first sent to Ozerlag on the western section of the BAM railway but Kolyma was always in need of additional prisoners. Gold production was more important than railways. Fidelgolts was sent to Kolym’a tungsten mines at Alaskinskaya just north of Ust-Nera in what is now Yakutsk, about 1,300 km north of Magadan.

Released from the mines

Fidelgolts caught tuberculosis. At the sick bay, they first thought he was pretending to be ill as his temperature was normal. The penalty for faking illness was high. Fidelgolts could risk execution. He was sent back to his hut with dire threats of what could happen to him. But the next day he coughed up so much blood that they believed his story and diagnosed him as having “scilicosis”.

Scilicosis was one of those illnesses for which the camp system assumed responsibility. So they had to pay for him to be taken to the hospital in Magadan and they had to see that things went fast. The first opportunity was a troop plane. The soldiers and guards had seats and the aisle was used for prisoners like Fidelgolts.

In Magadan they found it was not scilicosis but tuberculosis. That meant he should have taken care of the trip himself but it was already too late.

It takes months to treat tuberculosis but Fidelgolts recovered somewhat and was given easy jobs at the repair wharf in Nagaevo Bay. His health had suffered and so he was allowed to leave Kolyma in 1953. He had the choice of which camp he should serve the last part of his sentence in. He selected the warmest place in the Soviet Union he knew of, not far from Tashkent in Central Asia.

In 1953, Fidelgolts finally returned to Moscow. He had been granted an amnesty and was able to go back to his parents. He said that being back in Moscow made him feel like a newborn baby. Everything seemed so small, so new. His life had stopped when he was 20 but now it was time to start again, once he was well enough.

His parents found a place for him in a sanatorium for top party people. In his group, there was an NKVD officer who wanted to get to know him better and asked him where he came from. After Fidelgolts had told him, all interest subsided.

Fidelgolts really enjoyed the sanatorium’s good food. One of the other patients asked him if they could sit together in the canteen, explaining: “I am here for an eating disorder and when I see you eat so much, it brings back my appetite.” Fidelgolt accepted and his companion soon recovered fully from his disorder.

Revolt in Kolyma

At the end of the 1940s, there were new purges and lots of new prisoners were sent on the terrible journey to the mines. But times had changed. While the criminal convicts had once acted as assistant guards and had terrified the other prisoners unchallenged, the political prisoners were finally able to get their own back on the criminals. They were no longer just harmless citizens. Many had fought the Germans on the front while others had experienced action as partisans as when fighting the Red Army for Ukraine’s independence. For war veterans like these, the convicts were no real threat. In 1948, the political prisoners were separated from the criminal convicts. I do, however, know of cases where they continued to be in the same camp but this was the exception rather than the rule.

Prisoners in the cells sometimes took the guards hostage. In Magadan’s transit camp, it is said that criminal convicts once took over a watchtower. The guards shot at the prisoners with everything they had but when their machine guns ran out of ammunition, there were still lots of prisoners left and the guards were lynched.

A former prisoner told me how he had identified 32 informers and, for one of them, had used his influence with the convicts to allow him to survive because he knew he had a wife and children. He also suggested the man should have a “deep shave” which meant that, instead of executing him, they cut off both his moustache and his upper lip. “In that way, he could tell his friends and family why he looked like that!” And so that’s what they did. The other 31 were executed.

Next: Up to 1991