|

Period up to 1991

|

Dalstroi’s army, air force and navy staff went returned to their respective services under Moscow’s authority. Dalstroi’s ships were assigned to FESCO, the Far Eastern Shipping Company. The “Djurma”, for example, sailed to Magadan in 1968. The last prison ship “Odessa” was broken up in 2004. So all that is left is a scrap of metal from the “Dalstroi” which exploded in 1946 in Nakhodka. It can been seen in Nakhodka’s municipal museum.

All that remained of Dalstroi in 1958 was mine management and as that ceased its operations in 1968, the mines came under the authority of the Ministry of Natural Resources where they remain today. The staff were transferred too and instead of NKVD uniforms, they were first given other uniforms by the Ministry and then dressed as civilians. The mining authority was transferred to national combines which were later sold to private interests.

Kolyma made attractive

When the State is involved with people in the service of socialism, it is not usual, ideologically speaking, to give them financial incitements. But that was what they had to do as more people were needed in Kolyma. They told them they would be able to buy a car after a year or two. They were moved up the housing queue and told they would be given accommodation in attractive towns if they could hold out for a few years. And Kolyma’s shops were stocked full. But still people did not want to move there.

In a very popular film called “The Diamond Arm” a man from Kolyma pays for lots of food and drink for the other passengers on a cruise ship. He is the centre of attraction and, encouraged by the good cheer, bursts out: “Next time you should all visit me!” There was complete silence until one of the other revelers shouted: “We would like to meet again but it will be HERE!!!” That was as far as you could go in 1968 to show that Kolyma was not a very nice place.

Roman was a guard doing his military service at a transit camp in Nakhodka near Vladivostok, his home town. He began service in 1946 and when he finished in 1948, he decided that he might as well stay on and finish his political education in the party. He must have believed in the system and in the promises made in Stalin’s day but he was careful about what he said when interviewed.

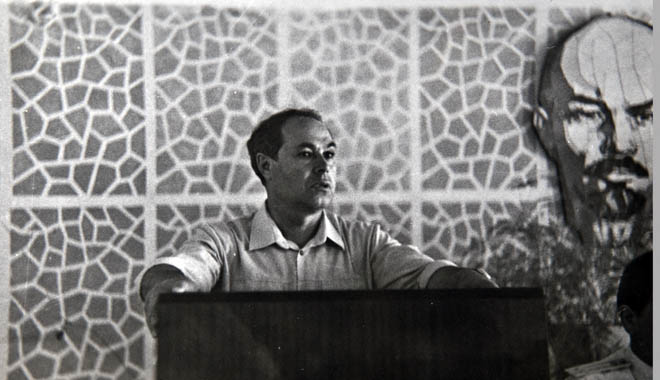

The good thing about a political education was that it was in Moscow, the most attractive city in the Soviet Union where only a few managed to move. Roman did well and became head of Komosomol, the young communists organization. Not long after, they needed more people in Kolyma. The party therefore encouraged young men from Komosomal to set an example by volunteering to go out there to work in the goldmines. As Roman was head, he was forced to set a good example for his colleagues and therefore had no choice but to “volunteer”.

Roman ended up in Susuman where he lived for 30 years and gained the grade of colonel as a political officer in USVITL, the prison authority. He raised a family and was respected by the town’s elite, including the mayor and the director of Susumanzoloto (or Susuman Gold). But he could not avoid “voluntary” work such as harvesting cabbage at the local collective farm.

Prisoners and guardians as neighbours

To a question about what it was like to live side-by-side with the prisoners who had had such a dreadful time in the camps, Roman answered: “The former prisoners respected us.” He seemed to mean it and he was partly correct. The prisoners knew only too well that many prison guardians kept their jobs in order to survive and others, like Roman, had had no choice.

For other former prisoners, respect was completely forgotten. One of them snapped: “I can remember what they looked like! I remember them so well that even if I have to wait for revenge in the next world, I’ll still be able to recognize them!”

The guards were given the status of war veterans. Depending on the number of years they had served in the camps, they were awarded war medals of different degrees which also affected their pension. As a result, most guards now have double the normal pension for their service “in the fight against fascism”.

Even so, many of those who had worked in the camps feel like victims. Over the years they had spent in the Soviet Union, they and their kind were the ones who had written the history and defined the nation’s development. They were respected citizens and enjoyed high recognition. Today they might have their additional pension, especially as it has Putin’s full support, while the prisoners get nothing. Dress parades, award ceremonies and invitations from distant towns to take part in memorial festivities have all ceased. The former prisoners just sit in their little flats and feel despised and deserted.

Rehabilitation was of vital importance to the prisoners. Without it, they were excluded from a good education, attractive jobs, membership of the party (a real disaster for confirmed communists). Their children could be bullied at school and excluded from further education and employment in strategic areas. Many were never rehabilitated.