From a historical viewpoint, the punishment system in Russia has always been draconian. Ivan the Terrible allowed his troops to go on slaughtering for days on end in Nizhniy Novgorod where only a small fraction of the population survived. It was simply because he feared the local princes would surrender their town to Poland, then a powerful state.

Sending political opponents to the remote corners of this huge realm, which was not quite as big under Ivan the Terrible, is also an old tradition. At the time of Ivan the Terrible’s so-called Muscovite Russia, the exiling of political opponents to the Solovki Monastery in the middle of the White Sea northeast of St Petersburg had been going on for years.

From the Czars to the Soviet Union

When George Kennan visited Russian prisoners and labour camps for political prisoners in 1885-86, he was horrified at the conditions. And they were said to be “mild” in comparison with those after the October Revolution:

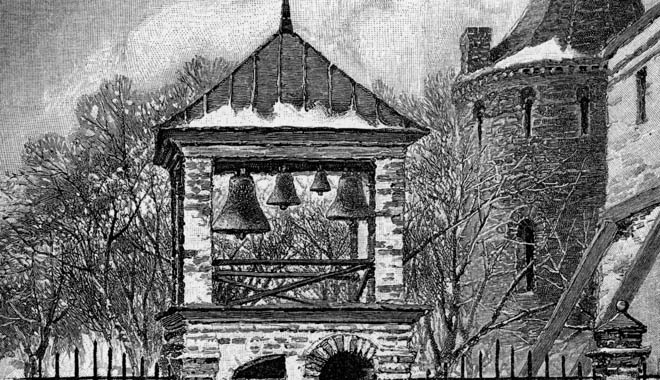

The first expulsion to Siberia was ordered by Czar Boris Gudonov. The church bells which signaled the attack on the Czarevitch (crown prince) Dimitri were sent off to Siberia (Tobolsk) in 1593. When exiling was discontinued “for ever” in the 1890s, these bells were symbolically the first to be allowed to return to Uglich where they had originated. They are still there but exiling was reintroduced in 1905 for people. Picture from Tobolsk 1885. Etching from a photo by George A. Frost.

The prisoners received wages from the state even if they did not work. They paid for their board from their own wages. Even if conditions were tough, survival was possible.

The journey to Siberia was on foot, in what they called "etaps" or "stages". A typical stage was 40 km. As the prisoners had money, the result is that today there are about 40 km between each village along the Transsiberian Railway. Every other night the prisoners were to be given a roof and after six stages there should be a least one day of rest when the prisoners could have a bath. Many of these stage prisons still exist today and are used as normal prisons.

The “modern” prison in Alexandrovski, not far from Irkutsk in eastern Siberia where the cells were labeled “good” and conditions considered “exemplary”. It is probably still in use today as only very few prisons have been built since the days of the Czars. Picture from 1885. Etching from a photo by George A. Frost.

A political prisoner in exile north of the tree line on the banks of the River Yenisei in central Siberia. Fridtjof Nansen took this picture during a voyage on the steamship “Correct” in 1913 when exiling had long been reintroduced. The exact conditions for the indivudual exile varied according to local authorities. Photo: Fridtjof Nansen, 1913.

The prisoners were allowed to take their wives with them into exile and the state paid for their journeys. The guards were required to provide for their transportation, typically by horsedriven cart or sledge.

It was terrible but nothing like what was to follow. It certainly cannot be said that Czarist Russia was a “moderate” let alone a free society, not even in comparison with other countries at the time.

It would therefore be wrong to conclude that the times of the Czars were “good”. A revolution was justified but the result was tragic and has left its bloody tracks across the world until today.

Next: The GULAG's beginnings